How to do Continued Stories and Next or Future Issue Teases

I was taught that if a story continues in the next issue, end with a climactic cliffhanger.

Well, duh….

And yet….

And, as I learned on my own, that “rule,” taught to me by Mort Weisinger, like pretty much all rules applied to creative work, is far from absolute. There are plenty of ways to go about continued stories. More on that later.

But first, the end-with-a-climax/cliffhanger way:

In the first issue, introduce the characters and establish their situation. Introduce the problem, threat, opportunity, whatever that generates the conflict. Develop the conflict to an intense climax/cliffhanger, and end there.

Second issue, elegantly, succinctly introduce the characters. Re-establish the climax/cliffhanger situation from the end of last issue. If possible, intensify the situation. Resolve the climax/cliffhanger—that is, brilliantly get Batman out of the death trap or whatever. Do it in such a way that A) the overall conflict is not resolved but is in fact increased, or B) a related-but-new, greater conflict arises to succeed the resolved conflict. Develop that new or increased conflict to an intense climax and bring the story to a resolution.

Or, you can end with another climax/cliffhanger and continue the story into a third issue.

And a fourth? Or more? There are no rules. But, you’d better be good if you’re going to continue a story that way for many issues. Keeping the dramatic tension building over many issues is difficult. And, the longer you make the audience wait, the bigger and better you’re going to have to make the final payoff.

The above is not a formula, by the way. No, I am not advocating formula writing. First of all, introducing the characters, establishing their situation, etc.—those are just elements of a story. Any story. Every story. Every Shakespeare play, every episode of Lavern and Shirley, every Michael Crichton novel, every Fleischer Popeye cartoon…etc. Hard to have a story without ‘em. They’re just the bricks. You can build a cute little Lego shanty out of them or the Taj Mahal. My Mother the Car or Hamlet. No limits.

And the technique of building to a climax/cliffhanger is just that, a technique. It’s the most often-used technique. How many times have you seen it done on TV when a show has a two-part episode?

And, by the way, it’s generally good policy to try to seamlessly weave your introductions and establishments the info into the action so it’s invisible exposition. And provide only the info necessary to understand the story in hand. I have to add that or some people assume that I’m advocating starting every story with a documentary about Spider-Man or whomever.

And, let me add, just in case, of course you continue to introduce/establish characters and what have you throughout the story. Uncle Scrooge is a miser every time you see him, not just the first time.

Get the feeling that what I say has been misconstrued a lot? There’s no end of examples out there of people repeating my supposed advice completely wrong.

Anyway….

Another approach to a story that continues over several (or many) issues is to construct each issue as a complete story, each story being a part of the tapestry of the overarching story. No cliffhangers. Just strong, one-issue, related stories adding up to a bigger story.

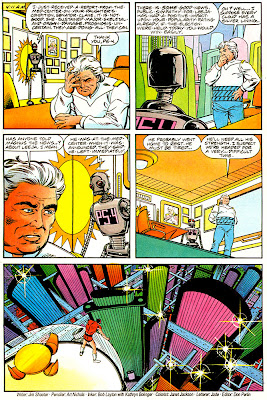

I used that approach for Steel Nation, a Magnus Robot Fighter story published by VALIANT. Steel Nation consists of four issues. Collectively, they tell the tale of a rebellion of freewill robots against humankind. Each issue has a complete story devoted to a phase of the war, and to the evolution Magnus undergoes as his eyes are opened to the justice of the robots’ cause. The stories are entitled “Protector,” “Soldier,” “Traitor” and “Savior,” which should give you a hint about the hero’s journey.

Later, a prequel, “Emancipator” was added.

As I said, there were no cliffhangers, though I did use teasers, especially important with that approach. Stay tuned.

Another approach to continued stories that you don’t see much in comics is the Hill Street Blues technique. Hill Street Blues was a TV show about cops. As I recall, in each episode, they started at least one storyline concerning one or more characters, they had the climax/conclusion of a storyline concerning other characters, and they had a “middle” of yet another storyline. Something started, something finished and something was in mid-development every week. And they kept it rolling that way.

Naturally, that technique is best suited for a group or ensemble.

Doesn’t have to be three stories lapping. Could be two or as many as in a Russian novel. But that’s a very high-degree-of-difficulty dive. Chris Claremont wandered off into Russian novel-like territory sometimes on X-Men.

Any more?

Sure. Run a continuing story intertwined with complete episodes of other stories. For instance, Green Lantern is involved in a multi-issue pursuit of Sinestro, but in each issue also deals with a villain du jour in a complete story—Star Sapphire one issue, Myrwhydden the next, etc.

Or, as Moench did with his best Master of Kung Fu story, a six-parter, issues #45-50 plus an epilogue issue, I think—he built each issue around the star and one principal member of the supporting cast as the overarching story developed, each issue teeing up the next.

Or Christopher Priest’s great Quantum and Woody blackout sketch technique, which told their tale over many issues in bits and bites from all over their lives.

Many other ways, including combinations of the above.

One of the great things about a serial medium is that you can do stories bigger than will fit in one issue. Getting readers to come back for the next issue is the challenge.

Not us. We’ll be back anyway, because we love this stuff, love the characters and it takes a great deal of awful to drive us away. But the new readers, and those on the fence? Them.

Or any general audience, less hooked on whatever than we are on comics. TV viewers, for instance. Yes, there are some people who will not miss and episode of Law and Order. Yes some shows survived and succeeded because of a dedicated fan base, famously Star Trek. But even the producers of Star Trek made the effort to reach and hold onto new people. That’s why the climax/cliffhanger technique is so popular. It’s effective.

But, for something that sounds simple and self-evident, in comics it’s often not done well.

I’ve seen this too many times: The writer takes us through twenty-one pages of set-up, what he or she thinks of as “human interest,” like hanging around the mansion drinking coffee, and maybe an action scene that’s trumped up so there will be an action scene. The hero stops a bank robbery or something. Something ultimately irrelevant to the overarching story. Then, on page twenty-two, Doctor Doom or some villain appears. Doesn’t do anything, just appears, looking menacing.

We get it. We know who Doctor Doom is. We know that this means trouble. And we probably didn’t mind spending a quiet day with the hero.

But the guy on the fence, or the new reader isn’t nearly as impressed, even if they know, or have an idea who Doctor Doom is, or intuit from his looks that he’s trouble. What it means to them is that they sat down to read a story, this issue—but, apparently the cool stuff starts next issue.

It’s not a cliffhanger. It’s a tease. And if what a new reader has paid four bucks for is twenty-one pages leading up only to a tease, there’s a fair chance they won’t have enjoyed the experience. Not nearly as much as we do, anyway. You know us. We enjoy Spider-Man stopping a miscellaneous bank robbery any old time.

The other way writers in these decompressed days blow it, in my opinion, is that they use a “shocking development” as if it were a climax/cliffhanger. To take a recent example, at the end of Ultimate Comics All-New Spider-Man #2, the shocking development used is that all-new Spider-Man Miles Morales discovers he can stick to walls.

I wasn’t really shocked.

Lots of us enjoy the discovery of whatever Miles’ spider powers are being played out. Is the shocking revelation that the new Spider-Man can stick to walls enough to entice a new reader to come back?

Well, who knows? The art is nice.

Once more, with feeling. There is no one way, no “right” way to go about a continuing story. But, as with any commercial endeavor, there are goals. Goals give us a yardstick with which to measure the efficacy of the effort.

You can’t argue with empirical evidence. One may criticize the writing on Star Wars IV, or the butchery that took place in the cutting room, but they got the job done, didn’t they? The many strengths overcame the weaknesses, like Biggs Darklighter’s death having less meaning because the earlier scene of him with best friend Luke was cut. (NOTE: I’m citing that from memory. It was 33 years ago that I read the screenplay. So feel free to correct me, SW-o-philes.

The comics biz at present is succeeding somewhat less well. It’s especially troubling because of that nagging feeling that we’re letting the ship go down without firing all our guns.

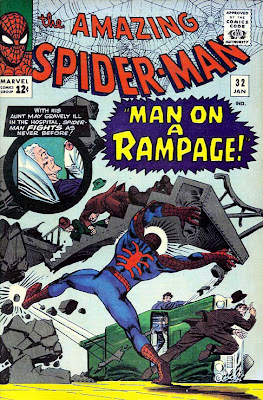

I remember buying this comic book at Churchill’s Pharmacy, corner of South Park Road and Brightwood Road, Bethel Park, Pennsylvania. It was October, 1965. I had just turned fourteen.

I read the book in the store, after paying for it. They were nice at Churchill’s but like everywhere else, if you read the books before buying them, they’d remind you “this isn’t a library.”

The issue contained the second chapter of a three-part story, fondly referred to around Marvel in my day as the “Master Planner Sequence.” This chapter, “Man on a Rampage,” features Spider-Man on a desperate quest to recover the only thing that can save his beloved Aunt May’s life, a serum called ISO-36, the only supply of which has been stolen by the Master Planner’s thugs.

The Master Planner turns out to be Doctor Octopus. Spider-Man ends up battling Doc Ock in his underwater hideout. Spider-Man’s desperate fury drives away Doc Ock, but their battle has so damaged the structure that, as Doc Ock flees, an immense piece of equipment topples over on Spider-Man pinning him under it.

He’s trapped.

The container with the serum lies tormentingly in sight.

The dome overhead is breaking up. Water is rushing in.

There is no way out. No hope.

For me, that was the best cliffhanger ever:

That’s just me. I’m sure you have your own favorites. But I won’t ever forget standing agape in Churchill’s Pharmacy trying to process the realization that I’d have to wait an entire month to see what happened.

As for the story, well, some would say it was amazingly coincidental that Doctor Octopus happened to need, and steal, the only thing that could save Aunt May. Stan did justify it to some extent, though. Aunt May was dying because of radioactivity in her blood. Her blood was contaminated by a transfusion of nephew Peter/Spider-Man’s radiation-altered blood. Like Spider-Man, Doctor Octopus gained his powers from radiation. It is not an inconceivable stretch that he’d be interested in a serum that affects radioactivity in the blood.

Yeah, I know, it’s still a coincidence.

But as I often say, you have to look at those early sixties stories in the context of the times. Back when Superman’s main problem seemed to be keeping Lois from guessing his secret identity, the emotional content of the Master Planner Sequence was stunning.

So Stan did that leg of a three-part continued story in the “normal” way, generating powerful conflicts, building to a climax/cliffhanger and breaking there. “As seen on TV,” you might say, since that’s the technique employed almost exclusively by usually-one-part TV dramas that have a special two-parter. It was/is the standard even for sitcoms.

And the pay-off was great:

Baiting the Hook

As noted yesterday, there are many ways to do multi-issue or continued stories. Not all involve a climax/cliffhanger.

If you don’t have that how am I going to wait a whole month to find out what happened cliffhanger? to bring the readers rushing back, how do you do it?

Lots of ways.

First, and ultimately the most important, nothing makes a reader more inclined to pick up the next issue than if the book they just read is great. That’s the mightiest hook you can sink.

If the book in hand is terrific, other kinds of teases may not be needed, but won’t hurt. If the book in hand is, perhaps, good, but not the greatest issue of all time, teases may help.

If the book in hand is bad, well, probably nothing you can do will work. But, if the teases are really compelling, at least there’s hope that the reader will give you one more chance.

The simplest tease is the next issue blurb. Even if it’s just the title, if it’s a really compelling title, that can stir interest.

I’ve know I’ve written a few good titles along the way. I can’t think of any right now. Maybe they weren’t that good.

Aha! I came up with one for Legion of Super-Heroes #42, in which the Legionnaires are in terrifying danger but have gotten new, protective costumes: “Fear and Clothing.”

Well, I liked it. And the editor laughed out loud.

Ahem.

Anyway….

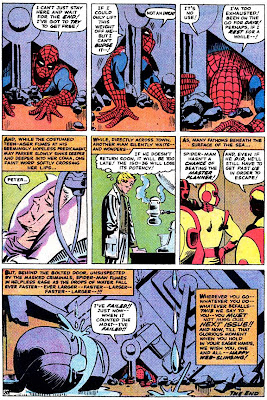

Some little hint about the must-see events that will occur in the next issue is good, too. At the end of Amazing Spider-Man #31, Stan wrote:

“Next issue: We shall learn the fate of Peter Parker’s Aunt May, as well as the identity of – the Master Planner!”

Okay.

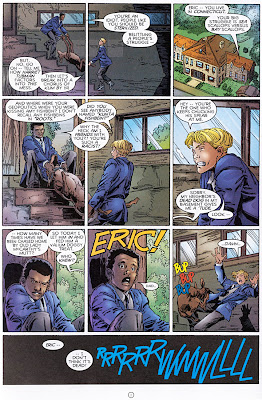

The next level of tease is, essentially, a dramatization of the next issue blurb/hint about must-see things in store—a page, a few panels or a single panel that plays out a dramatic development that affects next issue. In addition to his next issue blurb, Stan used that type of tease at the end of the first chapter of the Master Planner Sequence:

Stan was amazing. He had range. He was able to get me just as worried about Aunt May’s illness as he did about the coming of Galactus.

It’s a good thing. He didn’t offer a title for issue #32 and the next issue blurb admonishment “You must not miss it! ‘Nuff said!” is right up there with the lamest of all time.

If he had given the title of the next chapter, “Man on a Rampage!” I think that would have sold me all by itself.

But, as you see, other than for the usual problems he’s aware of, Spider-Man is hale and hearty. There is no intense, immediate, hero-in-peril cliffhanger.

Next issue blurb dramatizations are not limited to panels or sequences at the end, of course. Well-crafted panels or sequences not directly involved with or critical to the main story in the issue somewhere in the middle can be just as effective. The key term is “well-crafted.” If it’s good, clear and comprehensible as a portent of things about to happen that relate to the main story, it’s a tease. If it’s one of those what’s-this-and-what’s-it-got-to-do-with-anything? confusing bits, it’s bad writing.

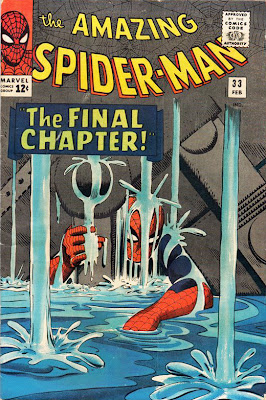

The Great Cover After the Best Cliffhanger Ever

At the request of Lincoln G, here’s the cover of the Amazing Spider-Man #33. Not surprisingly, the best cliffhanger also made for a terrific cliffhanger cover.

The best long term tease, the best tease of any kind is consistently great entertainment. Publishing compelling issue after compelling issue is the best way to keep people interested in what comes next. Build up enough momentum, enough reputation and even if the stories are not as good as usual for a multi-issue stretch, the audience will stick with a series for a while. It’s like a ride in a hot air balloon. You stay aloft for a while even after the burner is turned off.

I know you can think of lots of examples of the above.

So, besides being brilliant issue after issue, what can you do on a long term basis to entice people to stick around for future developments? Here are some techniques:

Slow Builds and Subplots

The slow build is cousin to the dramatized next issue blurb discussed last post. It’s a series of scenes unrelated to the story in the issues in which they appear that build anticipation of a story or Big Event to come some issues down the road. It usually goes something like this:

In an issue of the Fantastic Four (for instance) in which they’re dealing with the Super-Skrull, we cut to Doctor Doom’s laboratory in Latveria as he’s making an ominous scientific breakthrough. In the process, in very few words, we get across the essential info about Doom, that he’s smart and not nice. Uh-oh.

In a subsequent issue, in which the FF are battling the Frightful Four, we cut to Latveria again. Again, succinctly and elegantly we get across the essentials about Doom, plus the fact that he has discovered some frightening power. We look on with terror as he builds his Cosmic Pinwheel! That’s gonna be trouble…!

Etc.

Once we’ve built the anticipation to epic intensity, we pay it off with the Doctor Doom Cosmic Pinwheel Saga.

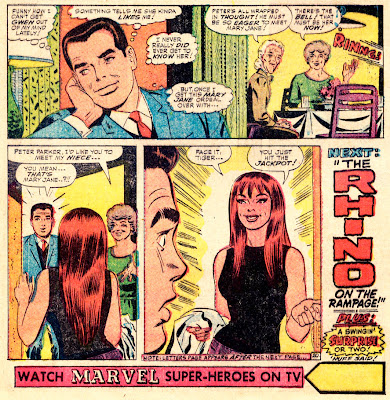

Those of you who have more comics easily at hand than I do can probably find many examples. One slow build I can think of, off the top of my head, that led to a Big Event rather than a story, was the slow build toward revealing Mary Jane Watson’s face in Spider-Man. I believe the first partial look at Mary Jane came in Spider-Man #25. After several slow build scenes along the way, we finally see what she looks like in #42: “Face it, Tiger…you just hit the jackpot!”

The above is different than a subplot. A subplot is related to the main plot of the story and is resolved at the same climax as the main plot.

An example of a subplot: In the movie Rocky, the main plot is the story of the fight. The principal subplot involves Rocky’s inner conflict over his self-worth. People think he’s nothing but an aging pug. Even he wonders if that’s all he is. When the bell rings at the end of the fifteenth round the main plot is resolved—Rocky loses on points—and in that same moment, the ding of a bell, the subplot is resolved—he is still on his feet, something no one else has ever accomplished in a fight against the champ, and therefore he has proven himself worthy. He calls his girlfriend’s name, all other threads are tied up. The end.

P.S. the champ says “no rematch,” and Rocky says “I don’t want one.” Which, of course, doesn’t prevent a slew of sequels. : )

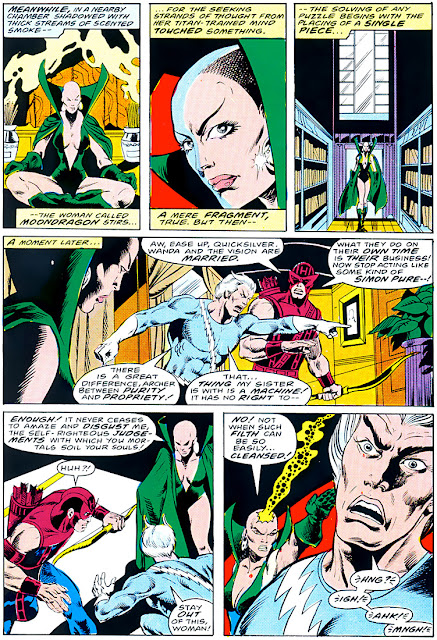

An example of a subplot that serves as a long term tease that comes easily to mind because I was involved was in the Avengers, in the Korvac Saga. In issue #175, Moondragon becomes actively involved in the search for the Enemy. Immediately, and in high-handed fashion, she pontificates to the Avengers about things. In particular, she lectures Quicksilver, who had a prejudice against “artificial” beings (established by others and related to the fact that he was upset about his sister, the Scarlet Witch, marrying an android, the Vision). “…eternity is vast—and its definitions of life are many.” Cosmic wisdom has she.

In the subsequent issue she disdains “…the self-righteous judgments with which you mortals soil your souls.” Then, using her mental powers, she simply erases Quicksilver’s prejudice!

Hawkeye’s reacts: “…where do you get off, baldy? Treatin’ someone’s mind like a…bathtub with a ring!” She’s high-handed, indeed, and oh, so smugly superior. She treats the other Avengers as subordinates, even leader Iron Man.

(All dialogue quoted above written by David Michelinie.)

We also get a hint that she gains some flicker of awareness of the well-hidden Enemy.

At Moondragon’s imperious insistence, the Avengers, who have been trying to detect the whereabouts of the Enemy using their powers, assemble and compare notes. A pattern emerges, as she knew it would. The Avengers find the Enemy hiding out in a modest home in Forest Hills.

A battle ensues. While the Enemy, who calls himself Michael, is distracted by the fight, Moondragon gets a glimpse into his mind…and is deeply moved by what she sees!

She does not join the fight!

At the climax, at the moment of victory, she reveals that what the Enemy/Michael had in mind for the universe was a sort of a benign dictatorship…not to “…interfere with our madness!” but “…only to free us from the capricious whims of eternity,” i.e., bad stuff.

She judges Michael the good guy and the Avengers, unwittingly the bad guys who “…slew the dream…then the hope!”

But she would think that, wouldn’t she…? Moondragon, who thought it was just fine to “fix” Quicksilver’s mind. Her take on what happened is colored by her belief that it is okay for “superior” beings like herself to make things better for us lowlifes.

She wipes the Avengers’ minds so all they will remember is a great victory. But she will remember what she thinks of as the tragedy they caused “forever….”

So, the subplot leads to a resolution for Moondragon at the same point that the main plot resolves, specifically that she has been changed by the experience. And might be up to something.

If I had continued on the series, I would have soon thereafter brought that bird to roost. As it happened, it was some time before I got around to it, in issues #219 and #220, in which Moondragon, emulating Michael, simply takes over a war-torn planet, forcibly bringing about peace.

(ASIDE: In reprintings of the Korvac Saga, long after I was gone, editor Ralph Macchio had an idiotic “Epilogue” tacked on that destroyed the ending, which he obviously didn’t grok. The Epilogue retroactively eviscerated the payoff of the Moondragon long term tease in issues #219-220, “…By Divine Right,” and “War Against the Gods.”)

Anyway….

A subplot can set up and tease a future issue.

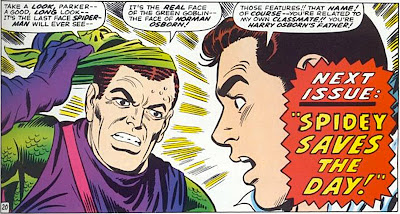

Of course, you can do a combination of subplot teases and slow build teases. Anticipation for the revelation of the true identity of the Green Goblin involved both slow build scenes and subplots played out over many issues of Spider-Man leading up to the ending of #39.

Another long term tease technique is the “Easter Egg.” Drop a small hint, show a potentially interesting item, or plant a clue, but keep it incidental and, at first, seemingly unimportant.

For instance, in an early issue of Spider-Man, Aunt May needed a blood transfusion. Her nephew Peter, who had the right blood type, volunteered. At the time, he briefly wondered whether or not the radioactivity in his blood would affect her. And as a reader, I thought, oh, my God…! Aunt May gets spider powers?

Nah.

It seemed to be nothing…until the Master Planner Sequence, in which the radiation that affected Peter positively turned out to be harmful to Aunt May, slowly killing her, in fact.

When the Master Planner Sequence came along, I remembered the transfusion bit long before. And I loved the fact that I did.

Easter Eggs are the most subtle of long term teases. I hadn’t been eagerly anticipating consequences of the transfusion, but when there were some, it helped to hook me even more on the series. It made it seem that everything mattered.

That’s how Easter Eggs work. You start looking for them, start wondering about possible consequences and speculating.

Gerry Conway used to plant Easter Eggs all over the place, usually having no idea (he said) what he was eventually going to do with them. Someone leaves a valise at the train station. Wonder what could be in it? A scientist detects something unusual. A strange gem is among those heisted in a robbery…. Whatever. Somewhere down the road, the secret plans for the Cosmic Pinwheel would turn out to be in that valise. Etc.

Writers often merely find some item or event that was a natural part of a story some issues back and find a way to retroactively turn it into an Easter Egg. The pen with which Doctor Strange signed the UPS guy’s receipt, an utterly incidental prop in a story about packages being switched turns out to now be charged by Strange’s touch with the Insidious Ink of Ichabodius. Or something.

Lots of ways to create and sustain long term interest.

The important thing is this: If you’re going to build up anticipation, suspense and high expectations, keep in mind that when the reader gets to the payoff, somewhere in the back of his or her mind, the reader is thinking, “This better be good!”